My exploration of AI in music is purely from a user perspective. In this article, I share selected experiments with a few compositions and allow for possible inaccuracies or simplifications in describing the process. The goal is to present observations and draw conclusions.

Today, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is becoming increasingly integrated into the musical landscape. Its capabilities are diverse, and several primary ways of working with it can be identified:

- Full Automatic Generation: With a single click, the AI can create a complete track with almost no human involvement.

- Working with Templates and Fragments: The system proposes musical options, and the musician assembles them into their own composition. The process resembles piecing together a mosaic.

- Refining Existing Tracks: Improving the sound, expanding the arrangement, and emphasizing details without altering the core musical idea.

- Vocal Input and Authorial Idea Development – This involves using an original audio sketch (vocal, melody, or instrumental phrase) as the initial basis, which the AI model then develops and arranges into a complete composition according to the provided prompt.

- Hybrid Approaches: When the composer combines their own ideas with AI suggestions or uses AI to expand musical phrases or even completed compositions.

- Other Methods.

Collaboration with AI is not a linear process but a dynamic chain of human creative actions that begins with formulating a prompt. The initial request is indeed an act of artistic intent: it defines the aesthetic direction, style, structure, and boundaries of the resulting work. However, precision in prompting is not the only path. Often, intentional ambiguity or an experimental character of the request opens up space for unexpected, unconventional outcomes that become part of the creative search.

Example of intentional ambiguity:Instead of requesting “A slow piano ballad in the style of Chopin in C major,” the composer might ask: “A slow, melancholic piece inspired by a sunset and a radish, in the style of jazz and trance.” Such prompts can encourage the AI to generate unique, unplanned compositions, arrangements, and sonic elements. Here, intentional ambiguity is used as a descriptive concept — one of the ways of working with AI that opens up space for experimentation and creative exploration.

The process of working with AI unfolds as a series of iterations and responses: the composer refines the prompt, reacts to unexpected ideas, reworks the model’s suggestions, gradually shaping the piece. Here, AI acts not only as a tool but also as a source of alternative pathways that the creator may adopt, transform, or reject. Yet the decisive role remains with the human: they define the concept, meaning, evaluative criteria, selection, editing, and finalization of the material. The finished work ultimately emerges from these artistic and aesthetic decisions.

Thus, AI expands the field of creative possibilities, but it is the human who sets the intention, direction, and final form of the work.

AI is a tool that expands the composer’s creative possibilities and helps encourage experimentation with music. But is this always the case?

On one hand, artificial intelligence truly opens up new horizons: it accelerates the search for textures, allows for orchestration modeling, facilitates experimentation with sonic combinations, and helps find unexpected solutions. On the other hand, if the author does not control the process and fails to set clear boundaries, the AI begins to dictate the result. The composer then risks turning into an operator of pre-made options rather than a creator of meaning and form.

AI can be both an amplifier of the author’s will and a duller of creative potential. Everything depends on who remains the architect of form and meaning: the human or the algorithm.

Practical Experiments with AI in Music Production

My work with AI has involved extensive experiments and research into its potential, driven purely by creative interest. I want to emphasize that the main body of my catalog under the musical name Gulan is entirely human-authored. AI integration, using the Suno model, was limited to a small number of recent compositions (2025), where it was applied exclusively to rework tracks released much earlier.

Starting from mid-December 2024, as I began experimenting with AI, I accumulated a considerable amount of unexpected and genuinely interesting experience.

For instance:

The track Space Projections pt. 2 (Uplifting Electronic Remake, 2025 Remastered) was assembled from AI-generated fragments. I was offered more than 200 variations, which I listened through, and from which I selected the necessary and highest quality ones. These selected fragments were then structured and arranged in the Digital Audio Workstation (DAW), where I also re-played some solo parts on a MIDI keyboard, using VST synthesizer sounds, and integrated them with the AI elements.

It is difficult to say unequivocally whether the new arrangement is an improvement over the original. Initially, the track was focused on atmospheric, near-cosmic minimalism and pursued a different goal: introspection. Now, in this new form, it has acquired cinematic and symphonic elements, directing the listener’s focus, as it were, “outward.”

When AI Leaves Audible Artifacts

Despite its impressive capabilities, the Suno AI model is still far from perfect. Even a beginner can often notice characteristic “artifacts”:

- A metallic undertone in vocals or sounds.

- “Shimmer” or unnatural movement in high frequencies.

- Compressed sibilants, over-processed, or slightly distorted mid and high frequencies.

- An overly “perfect” note placement—mechanical quantization, unvaried velocity, and rigid rhythmic positions that lack human nuance.

The mini-album Electronic Requiem features three compositions drawn from two of my older albums (Prologue, Electronic Symphony). AI suggested a multitude of fragments and ideas for each track. I meticulously listened to every suggestion, first supplying the necessary prompts. I then selected the most appropriate elements, filtered out low-quality material, and finalized the tracks in the Studio One editor. The album also incorporates an AI-generated female vocalize. The results were fascinating: the old tracks reappeared in a completely new sonic form, yet preserved their original essence: the core melody, harmony, and sentiment. However, the quality and clarity of this album’s sound leave much to be desired; the metallic whistling during climaxes is, in my subjective opinion, quite jarring. I hope developers solve this problem of “metallic screeching” very soon.

The Mechanisms of AI Music Detectors

General Principles of Detection

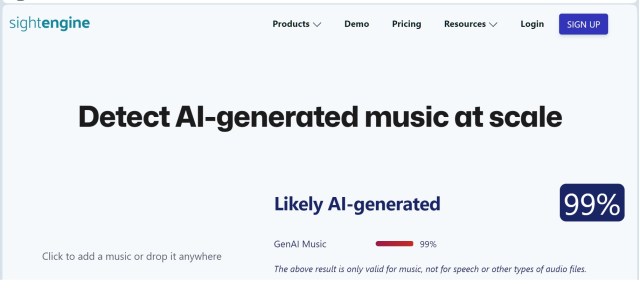

Different services may provide contradictory evaluations: while SightEngine focuses on spectral artifacts, the other two services (Letssubmit and MatchTune) rely on an analysis of musical structure (harmony and form). As a result, they classify tracks as human-made if their structural components (melody, thematic material) are original, and they do not rely on AI-related acoustic markers as the basis for a final conclusion:

- Focus on Acoustic Content: SightEngine works by analyzing the acoustic content of audio (including spectral features such as MFCCs), ignoring metadata. AI music models often leave subtle but specific spectral artifacts.

- Reason for Detection: The high “AI-generated” score is likely not due to the track being fully AI-composed, but because it contains pure synthesizer or heavily processed layers created using AI-assisted tools.

- Risk of False Positives: Like all AI detectors, SightEngine is prone to false positives. It can mistakenly flag very clean, “flat,” or repetitive human-created sounds and patterns (common in electronic music) as AI-generated because they resemble the spectral artifacts the model was trained on.

Case Study: “Spring Glade Lonely”

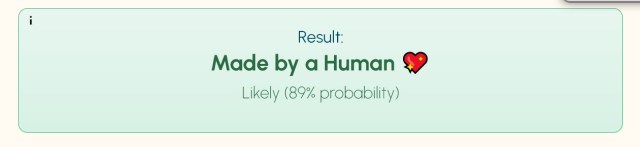

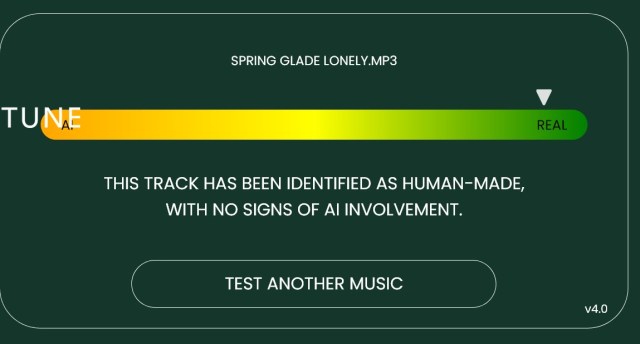

I tested my original composition, “Spring Glade Lonely” (from The Land of the Elves album, 2020), which I re-arranged using AI tools, on three different detector services. The results consistently highlighted the diverse criteria these services use to evaluate music:

Analysis Results: Letssubmit and MatchTune identified the track as human work, focusing on the musical structure (the preserved concept, melody, and theme). SightEngine reported a high likelihood that the track was “AI-generated,” confirming the principles outlined above.”

Despite the beauty of the arrangement and the rich ornamentation of the solo duduk line, artifacts like a “metallic” rattle are, unfortunately, present in some sections. Nevertheless, the final outcome was beautiful.

Case Study: “Voyage to Kussara“

Listening to another track, “Voyage to Kussara” (from the album The Land of the Elves, 2020), rearranged using the AI editor Suno. It turned out beautifully, except for some micro-distortion throughout the piece.

At the current stage, the only reliable method for solving sound-quality issues is having access to MIDI tracks and further refining the composition manually in a DAW. However, existing AI music models still do not provide such control, as they cannot generate editable MIDI structures with the necessary precision. There is a workaround: extracted audio stems from AI-generated music can be converted to MIDI using third-party software, but this process is often fraught with errors in notes and rhythm, requiring further painstaking manual correction.

Another nuance when working with older recordings is the original author’s conceptual framework. The composer shaped the track using the specific sounds and limitations of the equipment available at the time — and the overall concept of the piece was built “around” those sounds as well. As a result, an AI-generated reinterpretation may not fully reflect the subtle intentions embedded in the original work. It may achieve a richer, fuller arrangement, but lack the fine nuances tied to the composer’s initial sound palette.

On the other hand, there are cases where AI unexpectedly enhances the composition — revealing the underlying idea more clearly and allowing the musical concept to unfold in a way that was not technically possible in the past.

Legal Identification of Authorship

While detectors can analyze sound, they do not determine legal authorship. To secure rights, separate systems are used:

- YouTube Content ID – for copyright protection of music in videos.

- Identifyy and Amuse – for track registration and verifying authorship.

It is also important to note that, in addition to digital identification systems, Collective Rights Management Organizations (PROs), such as ASCAP, SESAC, BMI (in the U.S.), and others, play a key role in legally establishing authorship. These organizations record the legal ownership of a work by the composer and publisher for the purpose of collecting and distributing royalties from public performances of music (on radio, television, streaming platforms, etc.). Registration with a PRO is a fundamental step in formalizing copyright.

Copyright law faces challenges: legislation has not yet fully adapted to AI. In the United States, works entirely generated by AI without human creative input are not protected by copyright. If a human makes a significant contribution, copyright registration may be possible. Some initiatives propose labeling AI-generated content instead of traditional copyright protection. Most legal experts emphasize that AI is not a legal subject – the author is always a human. International practices vary, with the European Union developing global frameworks for AI-generated music.

Copyright and the Concept of “Hybrid Authorship”

The legal discussion continues: does authorship belong entirely to the human who conceives the work and makes creative decisions, or can the final product be considered a joint creation of a human and AI? Some researchers propose introducing new categories of copyright to reflect this complex co-authorship, where the human remains the principal subject, while AI participates in creating the material. At the same time, there is a discussion about the ethics of using training data-how appropriate it is to apply musical styles, vocals, or compositional models on which the system was trained, and whether the influence of original works on the final result can be traced.

Ethical and Social Aspects

The interaction between humans and AI in music raises questions about the distribution of creative roles. Studies show that many creators experience both inspiration from new possibilities and concern about the potential devaluation of human contribution. Another important issue is cultural representativeness: AI models are trained on existing data, and if these datasets are biased or one-sided, they may reinforce specific stylistic and cultural norms.

Responsible Algorithm Design

From a technological perspective, transparency in generative models is increasingly important: understanding how AI arrived at a particular musical solution and which data influenced the outcome. Transparency is not meant to dictate creative methods but to allow the human author to grasp the nature of the interaction and the degree of algorithmic involvement in the creative process.

Aesthetics, Authenticity, and Perception

The emergence of AI-generated music raises fascinating philosophical questions:

- Does AI-generated music feel emotionally authentic?

- To what extent does it reflect the individuality of the author if part of the work undergoes algorithmic transformation?

- Where is the boundary between stylistic imitation and genuine artistic expression?

Even though music created with the help of AI can have a strong emotional impact and move listeners, the philosophical distinction between the author’s personal experience and the algorithm’s imitation remains relevant.

These questions do not require definitive answers-they are part of the broader picture of contemporary music, where traditional composition, hybrid forms, and fully generative approaches coexist.

These reflections show that human-AI interaction in music is never just a technical process of sound generation. It is always a dialogue between the author’s intent, the algorithmic tool, and the meanings that listeners bring to the experience. Even when using highly advanced models, the central figure remains the human-with their intonation, taste, choices, and intentions.

Conclusion

Artistic decisions remain the responsibility of the human author. AI is a valuable tool that helps explore options and expand the creative field.

Andrei Gulaikin, 11/18/2025